🖛 This post contains ✨on-hover card images✨, indicated by the hanafuda card symbol, “🎴”, like so:

Thalia, Guardian of Thraben

🖚

🖚

I am a huge fan of card games, in general. The one that has held the lion’s share of my time and mindshare is Magic, legacy-format Magic in particular. I will eventually put down my thoughts on how to win at Magic, but this is not that post.

I was born a bit too late to play Magic on-release. I was one year old at the time, so, I probably wouldn’t have had the dexterity needed to shuffle effectively. I was born at just the right time to catch the beginning of some other card games, though: Pokemon and Yu-Gi-Oh. This post is about localization trivia about the latter.

This post is about the “Yugi-Kaiba Format”. Many of the rough edges discussed aren’t true anymore, and some of them stopped being true very quickly.

I am going to explain mechanics by alluding and comparing to what Magic does.

the manga

Yu-Gi-Oh is a card game, based on an arc from a manga also titled Yu-Gi-Oh. The plot of every early Yu-Gi-Oh chapter is as follows:

Introduce someone comically evil. Evil person threatens Yugi (the protagonist) and/or his friends

Introduce a game. Yugi and the evil person play that game with life or death stakes

Yugi wins; his opponent is driven insane or dies

In Yu-Gi-Oh (the manga), one of the games in one of the arcs is called “Duel Monsters”.

Duel Monsters is, in some early material, referred to by the less catchy name “Magic and Wizards”.

It didn’t have fleshed-out rules since it did not exist outside of the story, and the story isn’t really about Duel Monsters’ mechanical details. Yu-Gi-Oh (the card game) is based on Duel Monsters. The card game was produced by … 🥁… Konami, a famous Japanese game publishing company.

konami

Konami has some to-my-knowledge uniquely terrible labor practices 1 2 3! One of these practices is this one-two punch:

not crediting artists for their work on card illustrations

requiring all artists to sign NDAs! artists are not allowed to take credit for their work in any way

The “vibe” is, “by fiat, this game is a black-box created by Konami™. it does not contain artistic flourishes or influences by individuals.” This sort of a labor culture is not conducive to getting much primary source material about what working on the game was like, and why a design decision was made, which is a shame. There’s a wealth of information out there about how Magic is made now & how it was made in the past. I’m told some similar resources exist for Pokemon, though I don’t know this for sure.

jargon

Like many games, Yu-Gi-Oh has a bunch of jargon for its game concepts - kinds of cards, parts of cards, parts of turns, etc.

Yu-Gi-Oh lifted a lot of its gameplay elements from Magic one-to-one and just gave them a new, slightly different name. Examples:

Power ⇒ Attack

Combat ⇒ The Battle Step

Upkeep ⇒ Standby

Sacrifice ⇒ Tribute

They mostly did a thorough job of not 1:1 using Magic jargon. Except for how they named one of their card types: “Magic card”. Weird oversight! This was later retconned or renamed or amended to “Spell card”. It’d be cool to know what the deal is with this, but, due to how Konami’s implicit position is that the game does not have artists or a development process, probably we will never know.

relevant game mechanics

I am going to explain mechanics by alluding and comparing to what Magic does.

Quoting myself in “Pokemon Trading Card Game” design review:

An important idea in trading card games: over the course of the game, the amount of “swinginess” that happens in each turn should increase. The first turn should have puny little effects that represent tiny swings in “who is winning”. Later turns should have increasingly large effects & so large swings in “who is winning and by how much”. Analogous maybe to the “material advantage” bars shown by chess apps? Most collectible card games have a mechanic meant to achieve this.

Yu-Gi-Oh has the mechanic of “you need creatures to win. You can play one creature per turn. Larger creatures require you to sacrifice in-play creatures. So, large creatures cost cards and time.”

Yu-Gi-Oh doesn’t have mana. Most cards can be cast for free; the main resource, so far as I can tell, is card advantage. The pace / swinginess of the game is mediated by “normal summoning” and “stars”.

Normal summoning: you can play no more than one creature per turn. Loosely analogous to how in Magic you can play only one land per turn. Much like Magic’s land drops, there are ways to get around this “one per turn” limitation & play more creatures.

Stars: some creatures have a sort of psuedo mana-cost. Each creature has an immutable stat, its amount of “stars”. Things with a lot of stars are, (and these are the only game objects this is true of), not free. They cost “sacrificing some number of creatures”! Here is a list explaining what star counts correspond to what additional costs:

1★ to 4★: no additonal cost!

5★ to 6★: one sacrifice

7★ to 8★: two sacrifices

Observations:

There are three “tiers” of starriness, based on how how many sacrifices it costs to play the thing. You might expect there to be some sort of a functional distinction between, for example a 1★ and 4★, even if they both can be played for free. There is no such distinction. For all rules purposes a 1★ and a 4★ are exactly the same. weird! The cards in the manga have stars on them, roughly indicating how strong they are but otherwise having no associated mechanics. That’s why there are so many star amounts; they were flavor that had to be retrofitted to make them do something in an actual game.

I did a little bit of a fib when I wrote the above “stars to costs” table. On actual Yu-Gi-Oh cards, the stars are not represented by putting, e.g., “8★” on the card somewhere. Having 8 stars is represented by displaying 8 ★ symbols in a row. Humans can’t easily subitize past four of something, so, figuring out how many stars something has by reading the card is a pain in the ass.

In light of this, I’m going to redraw the “star to costs” list now, but this time I’m going to template it the way actual Yu-Gi-Oh cards present this information. I hear these days they’ve added creatures that have even more than 8 ★, so, good luck with that:

★ to ★★★★: no additonal cost!

★★★★★ to ★★★★★★: one sacrifice

★★★★★★★ to ★★★★★★★★: two sacrifices

Got it? Good!

- Wow! “two sacrifices”!? Those are some steep costs. You’re committing an extra two cards and two turns worth of summons, to cast your big shiny 7-star thing. There is no way this could be worthwhile to do. On one hand, a big expensive creature could be valuable if it sticks around for more than a turn. It might get to attack many times and so destroy several opposing creatures, which would be value, card advantage, etc. On the other hand, there are lots of 0-cost spells that basically read “destroy target creature”, so, the expensive creature won’t be able to do this.

localization

Yu-Gi-Oh’s first English-localized set is titled “Legend of Blue Eyes White Dragon”. I am going to refer to it as “E1”. When I talk about the first Japanese set (whose official name is “Vol.1”), I’ll be referring to it as “J1”. J1 and E1 are radically different.

E1’s contents don’t make much sense. It has 126 cards, here is their type breakdown:

╿ 126 cards

├─╮ 87 creatures

│ ╰─╮

│ ├─╮72 vanilla

│ │ ╰─╮

│ │ ├╼ 60 1★ to 4★

│ │ ├╼ 6 5★ to 6★

│ │ ╰╼ 6 7★ to 8★

│ ├╼ 1 "effect"

│ ├╼ 4 "flip effect"

│ ╰─╮10 "fusion"

│ ╰─╮

│ ├╼ 6 1★ to 4★

│ ├╼ 3 5★ to 6★

│ ╰╼ 1 7★ to 8★

├─╮ 36 spells

│ ╰─╮

│ ├╼ 15 "normal"

│ ├╼ 15 "equip"

│ ╰╼ 6 "field"

╰─╮ 3 traps

╰─╮

├╼ 2 "normal"

╰╼ 1 "continuous"I manually sorted the cards into these buckets to make the chart. I think visualizations like this are cool; I think it’s a shame there aren’t better automated tools for querying stuff like this.

mechanical oddities:

Stars (★) use an 8-point scale to represent a total of three possible states (“costs 0 sacrifices”, “costs 1 sacrifice”, “costs 2 sacrifices”).

Half the set consists of zero-cost vanilla creatures. They come three flavors:

their attack/defense are roughly ⚔100/🛡100

their attack/defense are roughly ⚔0/🛡2000

and “their attack/defense are roughly ⚔1500/🛡1500

It is weird that they want to spend sixty creatures worth of space in the set on expressing what are basically three ideas, especially since #1 is so underpowered nobody would want to use it.

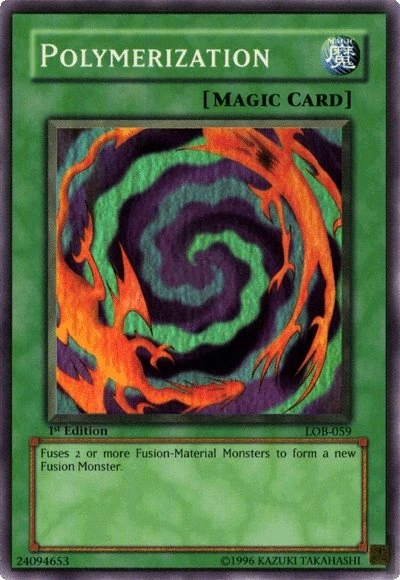

About 10% of the creatures are “fusions”. Fusion is a mechanic where you can summon specific creatures from out of your sideboard & without it costing you your summon for that turn. To do this, you cast a specific spell, Polymerization

, and sacrifice-or-discard two specific (as in, each fusion card lists exactly two other cards it is fused out of) other monsters as “fusion material”. Wow! Those are some steep costs. You’re committing three specific cards to do this, you need to find all three of them, one of those cards does nothing on its own, and the other two have no particular selling point other than that they can be used for this.

, and sacrifice-or-discard two specific (as in, each fusion card lists exactly two other cards it is fused out of) other monsters as “fusion material”. Wow! Those are some steep costs. You’re committing three specific cards to do this, you need to find all three of them, one of those cards does nothing on its own, and the other two have no particular selling point other than that they can be used for this.If you get a fusion out of a pack, you can’t use it unless you own the other three cards. If you get any fusion, you can’t use it without a polymerization. Polymerization is at one of the higher rarities; there is no particular reason you would expect to own it unless you went out and bought it third-party, which at this point is done out of mail-order magazines.

Fusions aren’t meaningfully stronger than their component material. They’re slightly stronger than their components, but the components are often really bad. You can often play stronger things of a given cost for free.

Much of the strangeness is downstream of how E1 is not “an english translation of the first Japanese set”. E1 is “assorted cards sourced from various sets printed in the first year and a half of the Japanese game”. And during the timeframe those sets were printed in, there was a fuckton of power creep.

The first Japanese set comes out in January of ’99. Sets continue to come out at a rate of about one per month. Which might sound deliriously quick to someone used to the Magic standard-legal set release schedule, but, these sets are small; 40-50 cards small. They’re also fairly reprint heavy.

- Fusion: The first set’s creatures are all vanilla. The second set introduces the first “not a vanilla creature” creature idea: fusion. Why does fusion get away with requiring you own a suite of four cards? Because it was way more plausible that “every player that wants this card, has it” when there are a total of like fifty unique cards in your game. Why does the mechanic seem sort of weird and weak? It was in the manga; they didn’t want to deviate from how it worked in the source material too much. It just, is not a very strong mechanic.

I am a bit curious about just how much each of these early sets overlaps with the other ones. The information is out there but it I don’t think anyone has actually analyzed it in this way. For that matter: I don’t think there are any tools quite on Scryfall’s level, here.

Regardless: Japanese Yu-Gi-Oh got lots of new sets over next few years. One of these sets came out in August of ’00. E1’s cards were sourced from Japense sets released between January ’99 and August ’00. That’s a year and six months and probably twenty or so sets and a few hundred cards.

Checking the exact number of sets is hard, due to the aforementioned lack of good tools

- J1’s strongest 4★ has an attack of ⚔1200. The set contains three ⚔1200 creatures. J1 had exactly one 4★; the limited cardpool forced you to include some 3★s and probably some 2 and/or 1★s also. The player probably does not have the ability to field playsets of all the ⚔1200 creatures anyway since there are no card shops or vendors other than “the vending machine the packs come from”.

By the time all the sets drawn on in E1 set had come out, the power level for a ≤5★ had risen considerably, in terms of how strong the individual options were, and in how many options existed. You no longer had to include a bunch of bad stuff just to reach the deck size requirement.

As for how the cards selected for inclusion in E1 were selected: my best guess is that the localizers were selecting for iconic-ness and for hitting a target amount of cards at each amount of ★s, even though at this point 1★ 2★ and 3★ were now basically design relics rather than meaningful content in their own right. The same is probably true of the fusions. It certainly wasn’t done to improve the play experience or average competitive relevance of a typical pack.

- The names on the cards are weird: this was often done in localization & not present on the originals!

Steel Ogre Grotto #1

’s name in Japanese is

’s name in Japanese is

鋼 鉄 の 巨 神 像 , or Kōtetsu no Kyoshinzō, or “Giant Idol of Steel”. Very sensible! In english we get a silly name. Another card in a later set gets renamed from “Iron-Fist Golem” to “Steel Ogre Grotto #2” to make sure the numbering isn’t done in vain. Baffling. I don’t really have a take on why this was done; I just think it’s interesting and would be easy for a casual observer to miss.

conclusion

Making a game is really hard.

resources

Format Library is a cool resource.

Goat Format is the most popular retro format.