Romhack Research

This post is about making an English translation patch for Yu-Gi-Oh! Duel Monsters 4, a Game Boy Color game from 2000 that—at the time I started—had no official English localization.

Motivation

As a kid, I had this game: “Yu-Gi-Oh! Dark Duel Stories”

It’s a card battler loosely based on the Yu-Gi-Oh card game. It’s the third of a four-game series and the only one in that series released in English. I wanted to try the fourth game: Yu-Gi-Oh! Duel Monsters 4: Battle of Great Duelist

I wanted to do so in English. This post is about how I made that possible.

That first part, try the game, is easy enough: go find the rom.

The second part, do so in English, proved harder. I looked the game up on romhacking.net.

I found one patch for the game. And it’s a translation! Let’s look at its specs:

Status: Unfinished

Release Date: 01 May 2002

That is not what we like to see! We wanted to see if there was a translation, and there is, but it’s unfinished, and if it has been over twenty years then the translator probably isn’t going to finish it.

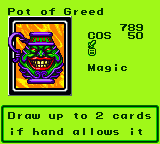

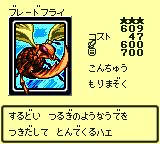

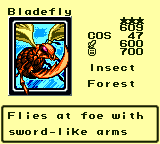

Still, the provided example screenshots look promising enough.

This is all in English and is understandable, if a bit stiff.

So, we grab the patch, patch the rom, yada yada, and then run the patched game. We have growing concerns:

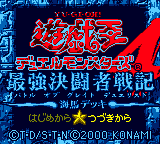

This is in Japanese. It would be nice if this was translated, but, most likely editing this is done by different means than editing the script and figuring out how to do it would have been a huge pain. And it would be for no real benefit since if you’ve gotten this far, you already know the game’s title, and can figure out “push some buttons; one of them will let me proceed”.

This is in Japanese. It would be more nice if this was translated. It likely wasn’t for the same reason the title wasn’t. There are a mere five choices, so, the player can figure out which is which and just remember. So this too is fine.

Incidentally, most of these options are just transliterated English words! Learning the kana and sounding stuff out is a much lower bar than outright learning Japanese. So if you burn to read these you could in short order.

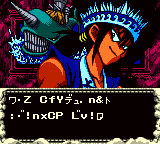

I had excuses for the other two screens not needing to be translated but this garbled text is absolutely getting in the way of my enjoyment. This translation has the in-battle text done, but, that’s not quite enough for a cozy experience since menuing is unavoidable.

I wanted to play the game and to do so in English. It looks like doing so will require translating the game myself, so I decide to do just that. It’ll be fun!

Let’s make a romhack!

I want to open up the game, pull out all the text, translate, and put it back. If possible, I also want to figure out how “non-text” assets are stored, and if it’s practical, edit these into being translated as well.

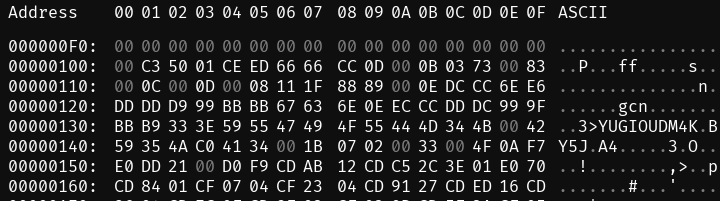

Let’s inspect the rom in our hex editor

First, let’s just dive right in with our hex editor and see if we can spot anything.

I pop the game open in a hex editor and quickly find it nigh-totally incomprehensible.

I see that somewhere around byte 130 there is some text, stored in ASCII, such that my editor can detect and decode it. It’s YUGIOUDM4K, which is probably the internal name of the game. It looks like it’s an abbreviation of “Yugioh Duel Monsters 4: Kaiba”. That’s neat.

But, when I scroll down through the rest of the rom, I don’t see more text. It’s either hidden or not there at all. I go googlin’ to try to find help.

🔎 how to romhack ↵

Some games have quite active fan/rom-hacking communities. I had hoped this would mean there is a ton of deeply detailed general-purpose guides out there that would handhold me through a lot of it. Such guides might exist, but I didn’t find them. What I did find was this extremely useful post: Data Crystal, on Text Tables.

A Text Table or

.TBLfile describes to a hex editor how to convert a ROM’s text format into readable text.

It gives this example:

Simple case

This is a purely made up example and don’t came from any game that I know of.

Using this TBL:

00= 01=A 02=B 03=C 04=DThis sequence

0x02,0x01,0x04,0x00,0x03,0x01,0x02Is decoded asBAD CAB

I learn that:

✅ I am now sure that what we want to do is to edit the ROM directly, byte by byte, rather than e.g. decompiling it

✅ The correct way to do this is to examine and edit it in a hex editor, as we are doing

✅ The first step of doing that is to figure out how text is represented

✅ Doing that is one and the same as building a .tbl file for the game.

✅ There is a solid chance that the developers did little or no obfuscation of how the text is encoded. The answer is probably about as simple as the example .tbl file above.

✅ I’m gonna want a hex editor with good support for .tbl files so I can apply them to the rom and see what I can find. I’m told ImHex is good, so, I install that.

At this point I have a guess as to why Mako’s textbox was all garbled. Which we’ll address later. I make a few weakass attempts at figuring out anything at all about the table using “guessing”, “probability analysis”, etc. I am unsuccessful. So, I go back to datacrystal for any further infos. What we find is quite a lot of info about each game in the series.

There are four games in the series. Some of them are helpful in figuring out what to do. So I can discuss them without ambiguity, I’ll name them based on their release order: DM1, DM2, DM3, DM4.

- Game Boy

- Yu-Gi-Oh! Duel Monsters → DM1

- Game Boy Color

DM1, DM2, and DM4 were only released in Japanese. DM2’s title is “Yu-Gi-Oh! Duel Monsters II: Dark Duel Stories”.

DM3 was released in Japanese and in English. In Japanese, DM3’s title is “Yu-Gi-Oh! Duel Monsters III: Tri-Holy God Advent”. In English, its title is… “Yu-Gi-Oh! Dark Duel Stories”.

I’ll refer to the English translation of DM3 as DM3-English, and the Japanese translation as DM3-Japanese.

I’ll call the unmodified, Japanese DM4 game “DM4”. DM4 has an incomplete fan translation. The translator/hacker goes by Chris Judah. I’ll refer to his game as DM4-Judah. Similarly if I need to refer to my game i’ll call it DM4-nyuu.

Finding DM4’s text table

imhex allows loading table files alongside ROMs, so you can quickly see what the stuff in the ROM decodes to, given that table.

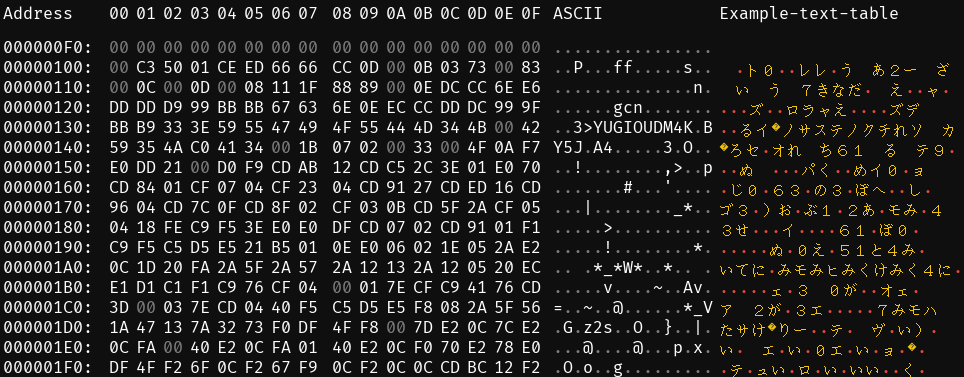

For a given ROM, there often is a “correct” table that, when applied, allows you to read text stored in the ROM. Our goal is to figure out what it is, which could involve trial and error via trying out tables we make up and seeing if we get anything text-like from them. Here is a demonstration of the sort of thing you might see while doing this:

The bytes are the contents of the rom. The “ASCII” column is builtin. The “example-table-file” column is a demonstration of what you get when you feed imhex a .tbl file: an at-a-glance view of what that table decodes the bytes into. In this example it’s the wrong table for this ROM, so we get gibberish.”

DM1 already has a publicly known text table. Here’s an excerpt:

00= 01=0 02=1 [...excerpted...] 0B=あ 0C=い [...excerpted...] AE=ペ AF=ポ

This looks pretty “generic”. Like, if the team I was working on handled their text encoding in this way in one game, I would not be all that surprised if they also did it in other, similar games. And these games seem superficially pretty similar to each other, and it is quick and free to try out tables. So we try this one.

Here is our status so far:

✅ We have a table

❓We don’t know where to look to see if it likely means anything

What we want is to find a location that contains text. Ideally it contains text that uses a large percentage of characters present in the script so we can solve as much of it as possible here.

The ROM is 4MiB, which is pretty small in most context, but in our context it is kinda large since that means there are 4,194,304 bytes. We’d rather not have to scroll through the entire thing.

Fortunately we do not have to do that. The data miners over at datacrystal (we aren’t done with them yet!) have already figured out where a lot of stuff is stored. Their findings on “where in the ROM are various things” is a “ROM map”.

I can only imagine that constructing the map must have been arduous. Thank you, people involved 🙏

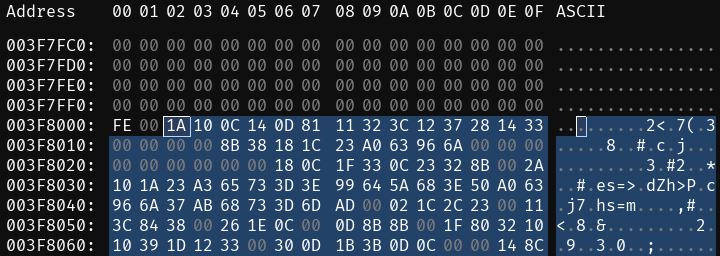

We can consult their rom map, which says addresses 0x3F8002-0x3FFE87 store “Cards Text”. That is, they’re where the flavor and/or rules text on the cards, as is displayed during gameplay, is stored.

What we expect we’ll find, when decoded, is a big block of text containing all the card texts one after the other. Probably either each card text will be the exact same length (that is, any unused space is actually represented by spaces), or, it’ll be one big run-on sentence and the demarcations are defined in a pointer table somewhere else.

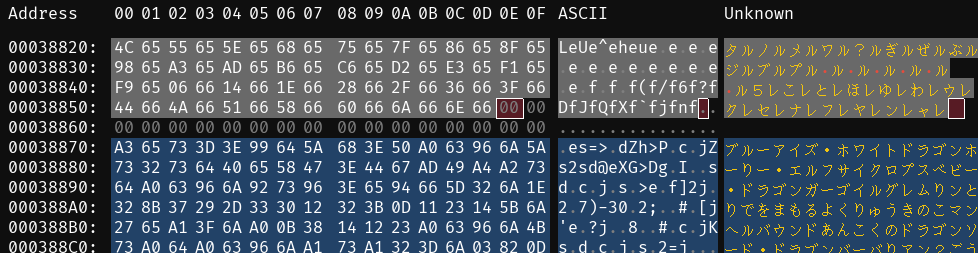

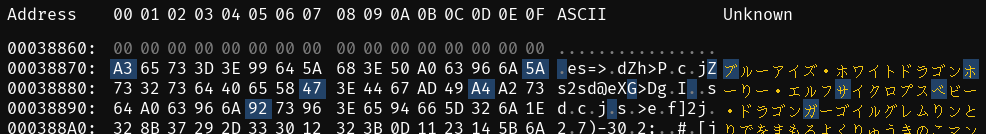

Anyway, here is what I see after loading the DM1 table at the start of the card text area:

That is definitely the card text, which is great. It looks like the internal ordering is the same as the external ordering, which is convenient since it’s one less thing to keep track of when yoinking data out or putting it back in at the end.

The first card is ブルーアイズ・ホワイトドラゴン. Its flavor text is supposed to be たかいこうげきりょくをほこるでんせつのドラゴン, which is what we see in the decoding we get from our .tbl.

So the table might be 100% correct. It’s definitely correct enough to get the kana right, which is enough to let us get started on making sense of and extracting this stuff.

Let’s learn about how the card text is stored

The list of card texts has a bunch of empty spaces between the entries.

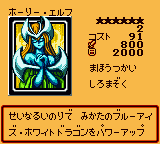

The first text excerpt is represented like this:

たかいこうげきりょくをほこる でんせつのドラゴン

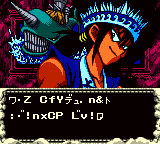

And here is what is seen in-game:

This singlehandedly probably tells us everything we need to know about how this is structured. In-game, card text looks like it is allowed to be up to 36 characters long, and has a linebreak in the exact middle. It looks like it’s probably stored in these 36 byte segments, spaces and all. We’ll check a few more to be sure though.

Here’s the second

せいなるいのりで みかたのブルーアイ

ズ・ホワイトドラゴンをパワーアップ

This fits the space constraints. It also aligns with what we see in-game:

Let’s check one more to be sure. Skipping ahead a bit, we find this rather decisive example:

なんぼんももっているハサミを

きようにうごかし あいてをきりきざむ

Compare with what we see in-game:

Now that we know how it’s stored, we know how to put it back when we’re done changing it. So, now we copy the stuff from 0x3F8002-0x3FFE87 as decoded by our table, for later translation.

I try editing one of these card texts and the change is reflected in-game. Check it:

We didn’t use any clever tooling here; we just manually looked at the table to find which byte represented each symbol we wanted. Then went to the part of the rom that defines what we want to change. In our example, we picked ブルーアイズ・ホワイトドラゴン’s flavor text. Then we edit those bytes so they now spell out whatever we wanted to say.

here is what it now says:

1337!!!?

おはよ インターネット

The second line means “hello internet”.

Let’s much more quickly learn about how card names are stored

The aforementioned rom map tells us card names are stored in 0x60014-0x63F4F. This is wrong, actually!

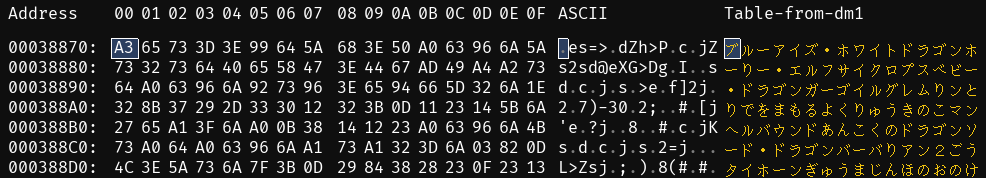

I was able to find it, though. It’s actually stored in 0x38870-0x3a66d:

Now, let’s figure out how it’s structured. We know (because of observation, testing, etc) that card names may be up to 18 characters long.

Looking at the first couple of bytes, we have:

The good news is this is legible. The bad news is it appears to be unstructured. We have a big chunk of memory where all the card names are stored one after another without any separators.

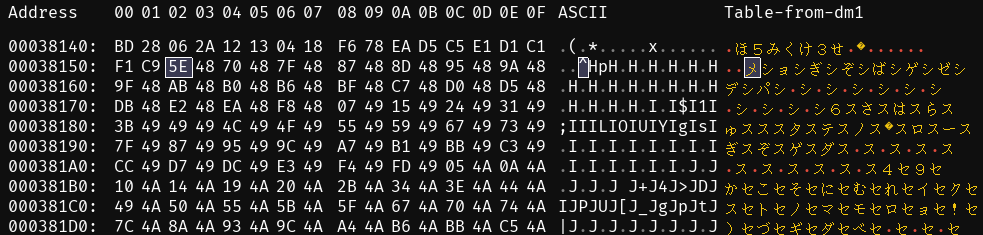

Before this chunk, we have a list of pointers that tell us where each card name starts relative to a base address. This region is: 0x38152-0x3885d.

The pointers are stored in a compact form, using 2 bytes each, and they represent how far away each card name is from the base address.

We realized this because when we looked at the data, the numbers didn’t make sense as absolute positions, but when we subtracted a certain base number, they lined up perfectly with where the card names actually start.

As it is, if we want to change the card names we’ll need to also be allowed to change the length of a card name. If we change the length of any card name, the starting positions of all the following names shift. To fix this, we need to recalculate the pointers.

Doing so involves figuring out how the game is turning the two-byte sequences into the memory locations, so we can, in conjunction with our list of new names, do what the game is doing, in reverse, to get the new pointers.

To find the actual memory address of each card name, we use the following formula: Actual Address=Base Address+(Pointer Value−Base Offset)

Read pointer value

- Extract a pair of bytes

- Interpret as a little-endian integer

Subtract the base offset (

0x4870)Add the base address (

0x38870)

However there is a complication. Here’s our data: 5E4870487F4887488D489548. To skip ahead a little: if we pull out the first pair of bytes 5E48 and apply our steps to it, we do not get a memory location corresponding to a card at all. Instead what we get is a pointer to the endpoint of the pointer table: 0x3885E!

Everything before 0x3885E is the pointers. Then there’s some padding, then everything past that is the card names. As such we can be pretty sure that this is a data structure. Such as a way of indicating when the list of pointers ends. Regardless of the why: we’re going to set aside 5E48 for now since it is a different kind of thing. Here’s our real data: 70487F4887488D489548.

Applying the process

1. extract pairs of bytes

70 48, 7F 48, 87 48, 8D 48, 95 48

2. interpret as little-endian values

0x4870, 0x487F, 0x4887, 0x488D, 0x4895

3. subtract base offset

Our values are spaced correctly but their absolute values are wrong. Normalize them to 0.

0x4870 - 0x4870 = 0x0

0x487F - 0x4870 = 0xF

0x4887 - 0x4870 = 0x17

0x488D - 0x4870 = 0x1D

0x4895 - 0x4870 = 0x25

4. add base address

Our values are spaced correctly and normalized. The data is supposed to start at 0x38870, so add that to each value

0 + 0x38870 = 0x38870

0xF + 0x38870 = 0x3887F

0x17 + 0x38870 = 0x38887

0x1D + 0x38870 = 0x3888D

0x25 + 0x38870 = 0x38895

You could combine the “base offset” and “base address” arithmetic into a single step. However, splitting them out makes it clearer why it works.

Applying our process gets us the memory locations 0x38870, 0x3887f, 0x38887, 0x3888d, and 0x38895. These should be the beginnings of the first five card names. Let’s see how we did.

Here i’ll misuse <ruby> to make the point. The ruby is the memory location. The text is the segment of text demarcated by that memory location.

Those are the actual first five card names! If you’re curious which ones, click on each and you can confirm. So we have a process. Do that in reverse and you can generate the pointers.

Now, let’s set aside the base DM4 for a bit. We are going to talk about fonts.

Messing with DM4-Judah

Here is what I said, earlier:

At this point I have a guess as to why Mako’s textbox was all garbled. Which we’ll address later.

It is now “later”. Judah was able to expand or replace the in-game font. The thing that would make the most sense, would be if he replaced the original font, or parts of it. So, any text that he didn’t edit at all, became wrong, since some of the characters in it got swapped out for random English letters and punctuation.

Let’s see if we can check whether that’s true. In the process of doing so, we’ll also work on the related matters of developing a font and of how the game matches the values in the .tbl to an image it draws on the screen.

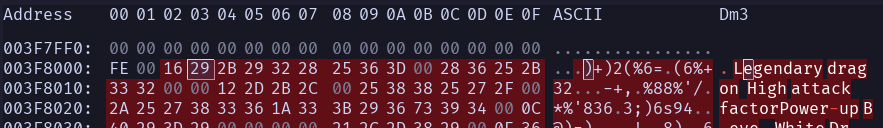

To probe DM4-Judah for hints we’ll need to, much like the base DM4, have a way of getting text out of it. We’ll need a character table. Let’s start by seeing if we can get out of having to create it ourselves.

DM3-English has a text table.

We can pop open his English DM4, load the English DM3 table, and check the same address as before.

What we see is his translation, of the first card. So, this table works. We’ll later find that this table isn’t a 100% match, but it is close enough for us to get started.

Character maps

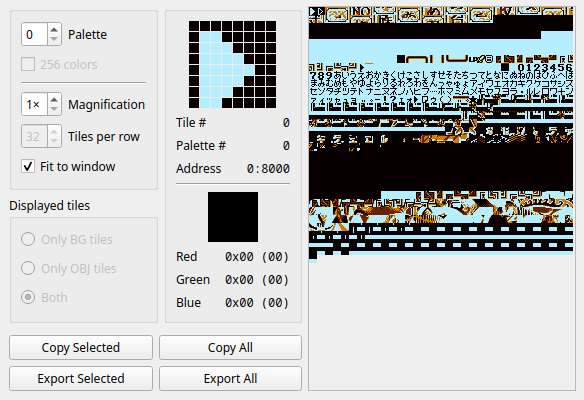

The gameboy uses a portion of its memory, the vram (video ram), to store small bitmap tiles, which are the building blocks for what’s displayed on the screen. each of these tiles is defined in the rom and represents a tiny segment of the overall graphics. at any given moment, vram is filled with tiles that the gameboy can use to draw the current screen, like a “word bank” but for visual elements.

Since vram is limited, all of the tiles in the rom can’t be loaded at once. Instead, based on the context (e.g. whether you are “in battle”, “in a menu”, etc) the vram contents are updated to contain the right stuff.

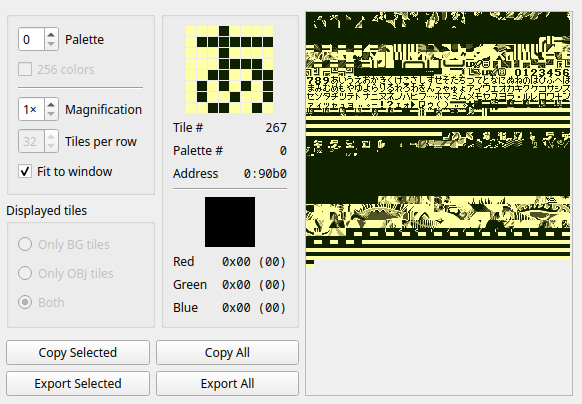

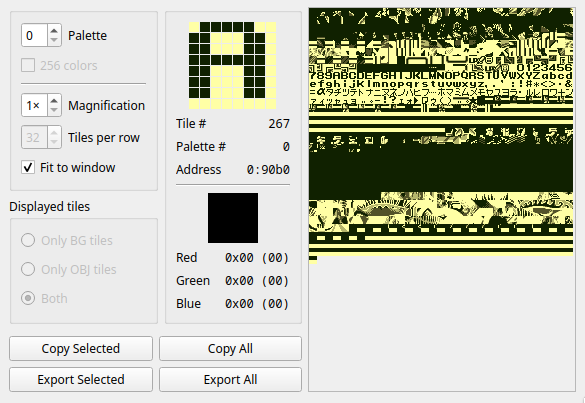

Once in vram we know exactly how the contents will look once they’re onscreen. mGBA (like many other popular emulators) has a “view tiles” feature. This lets us see a visualization of the vram’s contents, like so:

This tile data is the rom somewhere. We can’t, based merely on how it looks when loaded into vram, make any guarantees about how it is represented in the rom. If we could find it, and we knew how it was encoded, we could make changes to it, which would in turn change the “tile” in vram, which would in turn change the tile onscreen.

Let’s look at some tile maps.

Example 1: Bladefly (DM4)

We see stuff in a nice logical order: the order found in the character table, or at least pretty close to it.

Example 2: Bladefly (DM4-Judah)

This is quite similar to the base DM4 vram contents. It still has a bunch of the kana in it! It looks like Judah found the font and replaced some of the characters to have the english alphabet and punctuation.

Notable: he puts a bunch of punctuation in slots that previously had kana in them. This is why Mako’s text was garbled. It was encoded using the DM4 character table and was being decoded using the DM4-Judah character table, resulting in showing the wrong stuff.

Now, let us once again be carried by the extremely helpful articles on datacrystal. The font is stored at 0x20100-0x20510.

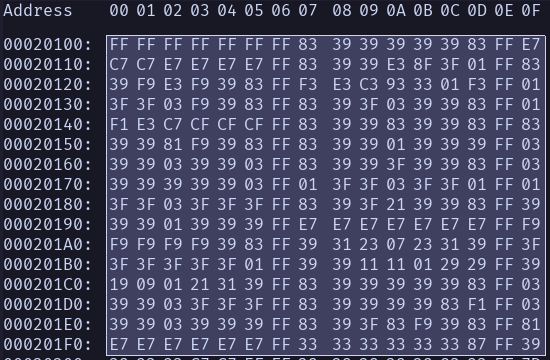

Here’s the first 256 bytes, 0x20100-0x201FF, from DM4-Judah:

This looks like it isn’t obfuscated. It looks like, if we’re very lucky, it might literally be a bunch of 8x8 bitmaps. Which, it turns out, they are. Here is how we can turn this back into an image:

0. pick an 8-byte segment

We’re going to use the second character as our example since the first one is pretty boring and unillustrative. as such we skip the first 8 bytes in favor of bytes 9-16

83393939393983FF

1. split into 1-byte segments

83 39 39 39 39 39 83 FF

2. put each byte on its own line

83

39

39

39

39

39

83

FF3. represent these lines in binary (as in, as 8 bits) instead of hex shorthand (as in, as two hex digits)

10000011

00111001

00111001

00111001

00111001

00111001

10000011

11111111Each byte is a an instruction: “I represent 8 pixels. When displaying me, turn the 0s on and leave the 1s off”. Let’s try taking this representation one step further to make it easier to read: we’ll replce the 0s with ▉s and the 1s with ╷s

╷▉▉▉▉▉╷╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

╷▉▉▉▉▉╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷Tada!

It’s not a fluke, either. Here’s the first four characters after being decoded in this way:

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷▉▉▉▉▉╷╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

╷▉▉▉▉▉╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷▉▉╷╷╷

╷╷▉▉▉╷╷╷

╷╷▉▉▉╷╷╷

╷╷╷▉▉╷╷╷

╷╷╷▉▉╷╷╷

╷╷╷▉▉╷╷╷

╷╷╷▉▉╷╷╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷▉▉▉▉▉╷╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

▉▉╷╷╷▉▉╷

╷╷╷▉▉▉╷╷

╷▉▉▉╷╷╷╷

▉▉╷╷╷╷╷╷

▉▉▉▉▉▉▉╷

╷╷╷╷╷╷╷╷Tada!

It looks like they’re even in the same order as is used in the character table. Like mentioned before, the vram or onscreen representation does not guarantee anything about how the data is represented internally. We are quite fortunate that the relationship between “position in the font” and “position in the character table” are so similar since it is less stuff to keep track of, but there was no guarantee it would be this way. DM4 stores its font in the same place.

As mentioned, DM4-Judah uses a character table similar to or the same as the one from DM3-En. It also uses the same font as DM3-en. With a bit of math and experimentation we can figure out which bytes correspond to the subset of the font changed between DM4 and DM4-Judah.

So, I do that: I find the parts that constitute “Judah’s font”. I copy their values from DM4-Judah and paste them into the corresponding locations in DM4. This unlocks a cool trick. We’ll call this modified rom “DM4-fonttest”. We can diff DM4-fonttest and DM4 to create a patch: a file describing how to produce DM4-fonttest when given DM4 as an input. That patch can be found here

So, now we are reasonably comfortable changing stuff and we’ve located and extracted the bulk of the text. Up next: translating it.